I recently picked up a book by Mart Laar called

The Estonian Way or

Eesti Tee. At first glance, it is a history book written by an Estonian holding a doctorate in history from the University of Tartu. Laar has authored many books on Estonian history, and has recently published three about the Second World War,

Sinimäed 1944,

Emajõgi 1944, and

September 1944.

After browsing through the latter three, I found them welcome additions to the history of the eastern front during World War II. But in the first book,

The Estonian Way, I was a bit confused -- this is the best word -- when I noticed that not only did Laar cover the period of Estonian history that included himself, but also addressed the actions of some of his longstanding political rivals, like Edgar Savisaar.

To me, this was both odd and normal. One could imagine any contemporary politician writing about themselves and their relationships with other politicians. But the historical backdrop gives the book the appearance of a history textbook that just happens to be authored by one of the major players in that history. It would be as if Thomas Jefferson wrote a history book about the American Revolution and ... oh, by the way ... he wrote the Declaration of Independence too.

What are we to make of these writings by a historian cum politician? Are they official history or just one version of history expounded by a restorer of the state? I think some in Estonia might easily confuse

Laari ajalugu with

eesti ajalugu. But

Laar ajalugu is but one component of a healthy debate about the past. There have been great debates about history, and indeed attempts by certain political parties to enshrine parts of history in law. But most of these debates have only led to more debates, or, on occasion, symbolic gestures from the state.

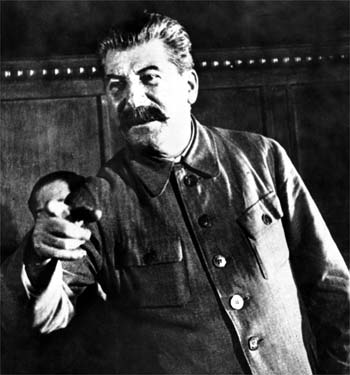

In a reconstituted state, the efforts to find a definitive new interpretation of history is fleeting. Under Stalinism, a genuine account of Estonian history could not be written. Since the mid-1980s, various trends have been discussed and the debate has enveloped younger generations for whom these events are actually quite immaterial to their daily lives.

At the very top, the state cannot leave this interpretation alone to historians, because, as we have seen, historians can wear other hats too. I was recently impressed with

a speech by President Ilves about the

soomepoisid, Estonian students who volunteered to fight in the Finnish Winter War and Continuation Wars.

While few, even in Russia, question the state's tributes to the Estonian Army of 1918 that liberated the country from Bolshevik and German troops, the role of Estonians in World War II is highly controversial. Even at the supermarket, you can find books about "Estonian soldiers through the ages" and World War II is represented by three uniforms -- the Red Army, the Waffen SS, and, in between them, a plain-clothes

metsavend guerrilla fighter.

In the thick of this, Ilves' approach stresses a) cooperation with Finland; b) personal sacrifice; and c) defense of democracy -- which seem to be recurring memes in his speeches, as much as Laar's work continuously references the partisan struggle as a symbol of Estonian resistance to foreign-imposed tyranny.

All of these values and ideas are part of a wider effort by Estonia's entrenched political generation to purify Estonians institutions -- it's army, it's parliament -- into a psychological unwillingness to surrender sovereignty or its values to external actors. Prime Minister Andrus Ansip struck a

similar tone recently when asked about his decision to remove one controversial war monument from the city center last April. For him it was about reassuring the public of Estonian sovereignty -- in other words, pushing a button the Kremlin told him not to push to prove that he is capable of pushing Estonia's buttons.

But in the midst of all this use of

ajalugu in politics, where does it leave, well, real

ajalugu, the work of non-politically aligned historians digging through Politburo archives or examining the failure of Baltic cooperation in the 1920s? In the book stores of the US you can read about the American Revolution from multiple sides. I am sure there exist even books about the Quebecois interpretation of the American Revolution. Do these perspectives exist yet in Estonian historiography and are they as well known among the public to the extent of the more politicized history?

All countries have [and need] their Thomas Jeffersons. They need their critical historians too.

I am in the US for the holidays and that means late night, alcohol-fueled debates about World War II and slavery. In an odd moment of compassion for our krautrock-loving German friends, I came to understand what a sad lot in life it is to be German and live with collective guilt for something you had no role in nor chose in utero to be associated with.

I am in the US for the holidays and that means late night, alcohol-fueled debates about World War II and slavery. In an odd moment of compassion for our krautrock-loving German friends, I came to understand what a sad lot in life it is to be German and live with collective guilt for something you had no role in nor chose in utero to be associated with.